USS Helena CL-50

Just before midnight on July 4th, the Helena and destroyers escorting troop ships and supplies moved into Kula Gulf and bombarded the beach for the last time. The landing of troops was successful by dawn of July 5th. But during that battle, we lost the destroyer Strong to a Japanese submarine that laid for us.

In the afternoon of July 5th, word came that the “Tokyo Express” was ready to roar down the slot.

The Maps of the Solomon Islands

| 1. Kolombangara Island where Capt. Cecil and others were rescued July 7, 1943

2. Kula Gulf were the CL 50 was sunk July 6, 1943 3. Vella Lavella were 165 officers and men were stranded be be rescued July 16, 1943 4. Ranongga Island were the remains of General Preston Douglas S1c USS Helena CL 50 were found in 2006. 5. Blackett Stright were John F. Kennedy's PT 109 was sunk August 2, 1943. 6. Randova Island PT 109's base. |

The information and map above provided by Shipmate Charlie McClellend, USS Helena CL-50.

On the evening of July 5, 1943, Helena joined up with the cruisers Honolulu and St. Louis and four destroyers.

Helena CL-50 (foreground)

St. Louis CL-49 (Middle)

Honolulu CL-48 (background)

Battle of Kula Gulf

USN vs. the Japs

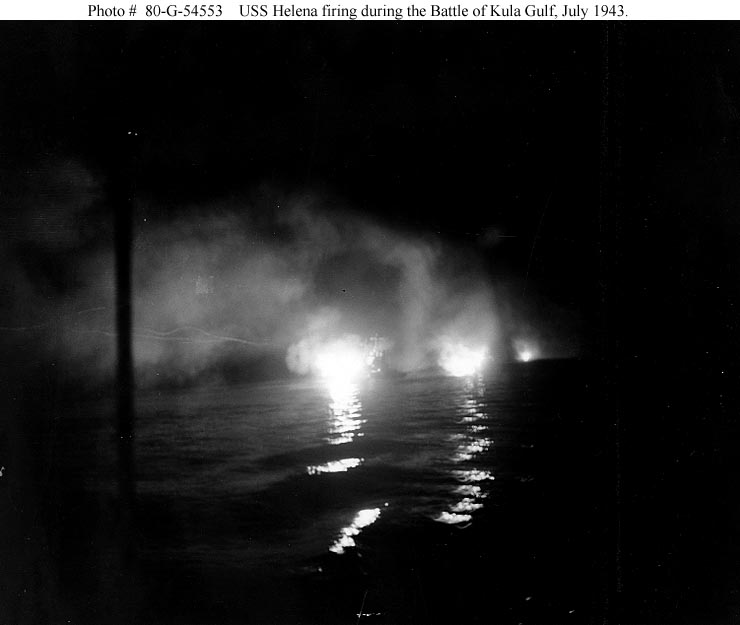

I had the 12 to 4 watch in the after engine room as chief of the watch with the chief of engineering, Lt Cmdr Cook. We were making 25 knots with all 8 boilers on line. Our radar picked up a column of Japanese destroyers at 0140 and, after our admiral put our ships into a battle formation, we commenced firing with our six inch guns. Our Captain Cecil went into rapid fire without zig-zagging like our previous Captain Hoover. Our big guns were firing so rapidly that the Japanese though that we were using some kind of secret six-inch machine gun.

While assisting the occupation in the Solomon Island Campaign the USS Helena was torpedoed and sunk off New Georgia Island in the early morning of 6 July 1943.

She was later awarded the Navy Unit Citation posthumously, for gallantry in action during the Solomon Island Campaign.

To read the citation, click here.

We set off to take on ten Japanese destroyers in Kula Gulf. The enemy destroyers were part of a reinforcement group which intended to land additional troops and supplies on Munda. We were part of Task Force 18, under the command of Rear Admiral Walden L. Ainsworth. I served with Admiral Ainsworth when he was the Executive Officer on the Mississippi many years earlier. Our battle group went to General Quarters at midnight and the Helena prepared for its third major engagement with the Tokyo Express.

This image is thought to be the last picture taken before she was sunk.

THE LAST BATTLE of the U.S.S. HELENA

Painting

by Tom W. Freeman

Used with permission. William Henderson.

One big disadvantage for us was that we were using gun powder that was not flashless. We were totally illuminated to the enemy and presented them with an easy target every time our guns fired, which was nearly continuously. The other cruisers had flashless powder. We had used all of ours up during the preceding day’s bombardment. After seven minutes of rapid fire, in which our gunners fired more than a thousand rounds, we sank two destroyers. I heard over the head phones, “Two down, one to go!” Then we were hit up forward by a “long lance” torpedo which blew off our bow and took our number one turret with it. One of the enemy destroyers had rapidly maneuvered within range of us and launched four torpedoes. All of our “black gang” shipmates in the forward engine room were killed. About 1 minute later we were hit by a 2nd torpedo. This knocked out all our lights and steam to the after engine room.

Chief Engineer Cook tried to get communication with the bridge. After we had tried every J.V. phone and no one responded he gave the order to open the steel hatch so we could get out of the engine room. We all got out of the engine room and tried to close the water-tight hatch, but the air pressure escaping from the engine room kept us from closing it tight. Then the third torpedo hit right under us and water hit us all and sent us flying in all directions. The ship’s back was broken and we knew that we didn’t have much time to get up on deck. Sea water was rushing in so fast that we couldn’t close the engine room hatch. The only light we had was from weak flashlights and battle lanterns which only made our situation even more frightening. A torrential stream of water followed us as we struggled to get to the upper decks. We barely cleared the next compartment. The intense water pressure knocked me from the port side to the starboard side and then back again to the middle. That compartment filled up quickly and we were all trying to get out through an 18” hole called a scuttle. By the time I got to the ladder the water was about 3 feet from the ceiling and one person was ahead of me on the ladder. Someone on the deck above us tried to close the hatch on us but we twisted the wheel out of their hands. By then I was getting desperate and as soon as the hatch was open I helped the guy ahead of me with a good boost. It was one of our junior officers climbing too slowly so I pushed him through the hole with as much force as I could, one of the few times in my career that I had a chance to push an officer around. The water was only a foot or two from the overhead when I cleared the compartment. The next day, after we were rescued, I was talking to Lt David La Hue, our junior division officer and he said “some son-of-a-b----- hit me in the ass and knocked me clean through that scuttle.” I admitted that it was me and I was in a hurry. We both got a good laugh.

The Rescue

I got to topside and lay on the quarterdeck for about 10 minutes, watching the firing going on from the other remaining ships. Then all was quiet, the night was very dark, not even the stars were showing. The ship started cracking up forward and someone said “we better get some of these rafts in the water.” That’s when we all realized that the ship was going down. Then I realized that I had no life jacket, I left it in the engine room. A second class machinist mate, George Schoolman, said “that’s alright Klepps, we can hold hands and go over the side together.” So we held hands, and jumped. Of course, our hands were separated on impact with the water. But we both managed to get on the same raft. As soon as we did, the brass 6” powder cases began to fall off the ship and onto our raft. We had no choice but to abandon that raft. I wanted to get as far as I could from the ship so as not to get caught in the suction when it sank. We could see the stern of the ship slowly going down. Fortunately for us there was almost no suction. I watched with a heavy heart as the ship which had been my home for almost four years, the “Happy Helena,” disappeared beneath the Pacific. I just couldn’t take my eyes off of it until it finally went below. Then I thought I better get on a raft. So I was looking around for a raft but they all floated away from me while I was so enthused with watching that ship go down. Then I knew I was in real danger of drowning. Being a good swimmer, I kicked off my shoes and began dog paddling. It seemed like I dog paddled for about an hour. I found myself alone in the dark of night in an oily sea. Once again, I realized that I was in danger of drowning as I grew tired. I was ready to give up and sucked in some water, but the oil made me gag and I spit it out. I made up my mind then and there, that with God’s help, I was going to survive. I really prayed in earnest for the Good Lord to save me and kept dog paddling for about another hour. Then, like a miracle was happening, I heard voices in the distance. I swam over to the voices and found 4 life rafts that were tied together. My prayers had been answered. There were only 48 men on all four rafts. It seemed about 30 minutes and we saw a destroyer approaching us in the dark. At first all we could see was a silhouette and we hoped that it was one of ours and not Japanese. Fortunately, it was one of ours, the Nicholas.

USS Nicholas DD-449

They had the small 20 mm guns trained on us, just in case we were the enemy. One of the seamen had a flashlight and signaled CL-50, our ship’s number. They said they would be right back; they still had enemy ships in the area, and were going to pursue it. They kept their word and returned in about ˝ hour and had thrown nets over the side to help us climb aboard. I had received quite a jar in my left knee when the 3rd torpedo went off under us, and had to be helped to climb up the cargo net. My knee was much better in a few days. After boarding the destroyer Nicholas, I went below deck, all dripping wet and covered with fuel oil.

Many years later when writing this, while lying awake at night it came to me that the Good Lord was watching over me when I swam away from that first raft I was on. George Schoolman, the guy who held hands with me as we jumped overboard, ended up on a different raft. They floated 3 days in the hot sun before they reached an island. When I wrote to him over 50 years afterward, he told me what torture they went through in the rafts. They were almost blind from the sun and oil in their eyes from the ship. He never told me how many men died from exposure and bites from sharks. I was lucky to be picked up the same night by the destroyer Nicholas, or should I say “Thank you Dear God for watching over me.”

The men treated us royally, offering us dry clothes and even a cigarette to calm us down. Smoking is never allowed on a cruiser, but these gunners didn’t seem to think anything of it, even while taking care of the guns. After being picked up, the Nicholas picked up a Japanese destroyer that was trying to sneak out of Kula Gulf. I went out on deck for fresh air just as the destroyer went to flank speed and began firing again. We were still in battle. Hot five-inch shell casings were being flung out of the turrets and landing next to me. I found myself jumping back and forth trying to avoid the shell casings and the rotating turret. The noise and concussion was knocking me down. Talk about being between a rock and a hard place! I finally got below deck and out of the way. They launched 4 torpedoes and claim to have gotten 3 hits on the enemy. Then they pumped about 50 5-inch shells into the Japanese ship. The destroyer Nicholas took us into a small harbor between Tulagi and Guadalcanal.

We got to the harbor at Tulagi and began linking up with other survivors of the Helena. Of the 900 men who served on the Helena, 168 were lost. A large number of out shipmates had clung to the bow section of the ship when it floated to the surface from the ship’s wreck, a miracle in itself. Life rafts were dropped to them by a rescue plane and the men drifted for several days to the Island of Vella Lavella. Others made their way to New Georgia and other scattered islands of the Kula Gulf. All the islands were occupied by the Japanese. Friendly natives, missionaries, and coast watchers helped the survivors evade the Japanese and sheltered and fed the American sailors until they could be rescued. For those who didn’t make it to the islands, death took them in the shark infested sea as they grouped along in the hot sun while half-blind and sickened from the oil which had covered the water when the ship went down. On July 16, 1943, the last of the survivors were brought back. They had survived a ten-day ordeal. The Helena earned seven battle stars and would be the first ship honored with a Navy Unit Commendation.

We were finally able to clean up while ashore at Tulagi. The only thing which could get the oil off our skin was a new product, Lava soap. More than a month later, at the Mare Island Navy Yard, I reported to sick bay with an ear ache. The corpsman relieved my discomfort by removing a large glob of oil which was lodged deep in my ear. Oil from Kula Gulf had gotten trapped in my ear, hardened, and became infected. Once the oil was removed, I was okay.

The survivors were put on our sister ship, the USS Honolulu.

A Wedding

We came back to the states in a Kaiser cargo ship that was converted to a transport with bunks 4 high. Almost 800 Helena survivors, plus others came back to San Francisco on the “Lew Wallace.” It took us 22 days, top speed was only 8 knots. The ship was empty and for the first couple of days, every time we came down on a big swell, there was a big bang. All or most of the survivors made a dash for top-side. It is better known as “torpedo fever.” The ship was all alone after the first day that we left Espiritu Santo harbor. After reaching San Francisco, I was assigned to chief’s quarters at Mare Island Navy Yard to await further orders. I was given 30 days leave and I immediately phoned home and said to Alma, “let’s get married.” She agreed and I asked her to make arrangements.

It was a lot to ask but her mother was able to get plenty of meat through her favorite butcher, Julius Lojeske. My brother Adolph was able to line up plenty of whiskey and beer. Everyone pooled their ration cards for the feast. Alma and I took blood tests when I flew home and Pastor Meyer agreed to marry us on August 28, 1943. We got our license at Bristol City Hall for $1.00, half price for servicemen. I always kid Alma I got it so cheap because she was so little. She weighed less than 100 pounds and had a 20” waist. We had a nice wedding and rented a small hall on Burlington Ave. Community Hall I believe it was called. We had 2 accordions for music, a father and son team. I don’t think my father missed one dance; he would grab any woman that was not dancing. He loved to dance the polkas and obereks.

The wedding ceremony was very nice, Alma had 3 bridesmaids and I had 3 ushers, Steve Kasper, Arnold Tonn and Art Wondrovski. My nephew Howard Arndt was best man. He seemed more nervous than me. We were the first couple that Pastor Meyer married during World War II. We had pictures taken in a Bristol studio after the wedding. We hadn’t made any arrangements for a hotel, and Steve and Lucy Kasper offered us a bedroom, so we spent our first night at the Kasper house. We were home only about a week, and then had to get back to California.

While I was home on leave I was contacted by Mary Treadway Washburn who was a Bristol girl married to Lt. Steve Washburn, Jr. Lt. Washburn was from a prominent Plainville, Connecticut family and had been an officer on the Helena. He did not survive the ship’s sinking and she wanted to know if I had any further information about her husband’s death. I felt so terrible for her. All I knew was that Lt. Washburn was one of the men clinging to the ship’s bow. He told a sailor next to him that he was a good swimmer and that he was going to try to swim to the island of Kolomabanga. The island was at least ten miles away which would have been a challenge for the best of swimmers. He swam away from the bow and was never seen again.

Action Report.

(Information found on the back of the picture)

Americans rout Japanese in two-night battle of Kula Gulf, July 5 and 6, 1943.

Wounded transferred at sea-Agroup of survivors of the USS Helena, picked up by an American destroyer, are transferrer to another U.S. warship at sea.

A wounded sailor is being carried across t he gangplank between two ships. (The Nicholas left, to the Honolulu.) August 14, 1943.

They were good to us, someone even gave me a pair of shoes to replace the ones I kicked off while swimming. They took us all back to Espiritu Santo, our home base, where we waited for a transport to the States. There was a small store there, and they gave us each an allowance, $100 I think it was, to buy new clothes. Being a chief petty officer I was assigned to the “Seabees” chiefs barracks. They treated me royally for 2 weeks. Every night before I turned in to my bunk, the head Chief would give me half a water glass full of “torpedo juice” as they called it. It was 90-proof sugar alcohol mixed with lime juice, and did that relax me for a good night’s sleep. My nerves needed it after the ordeal we came through.

"The Final Muster"